Scientific Journal Writing – No Easy Task

September 11, 2023

Since 2011, the Crawford Fund has been presenting Master Classes in Communicating Research, which cover in about six days a range of skills that scientists need to communicate their work to a general audience. Participants have come from across the Pacific, Asia and Africa and in each region the need has been expressed for specialist training for greater acceptance of papers in scientific journals – a whole different set of skills. Recently, mentor Dr Chris Beadle carried out capacity building for Indonesian scientists writing papers for international journals and his report follows:

A book “Sharing Knowledge: a Guide to Effective Science Communication” published 20 years ago by Julian Cribb and Tjempaka Sari Hartomo contained the following: “it has been claimed that up to half of the world’s scientific papers are never read by any other than their authors, editors and reviewers, and 90 per cent are never cited”. Twenty years later, and with the huge increase in the number of scientific journals out there, it’s likely worse, and with open access you may be paying lots of money and not getting cited, and self cites don’t count!

So, an essential rule when it comes to scientific paper-writing is that the author(s) must capture the readership you (they) are after, and in a way which persuades that readership to use the paper you are writing, and cite it in their publications.

This is no easy task, and as most journals now require papers to be written in English, even more difficult if this is the author’s second language.

If you want to learn how to give yourself the best chance of getting your paper accepted, signing on to a paper-writing workshop or tutorial when you are ready to write gives you an opportunity to work with a mentor who can keep you on track throughout the writing process.

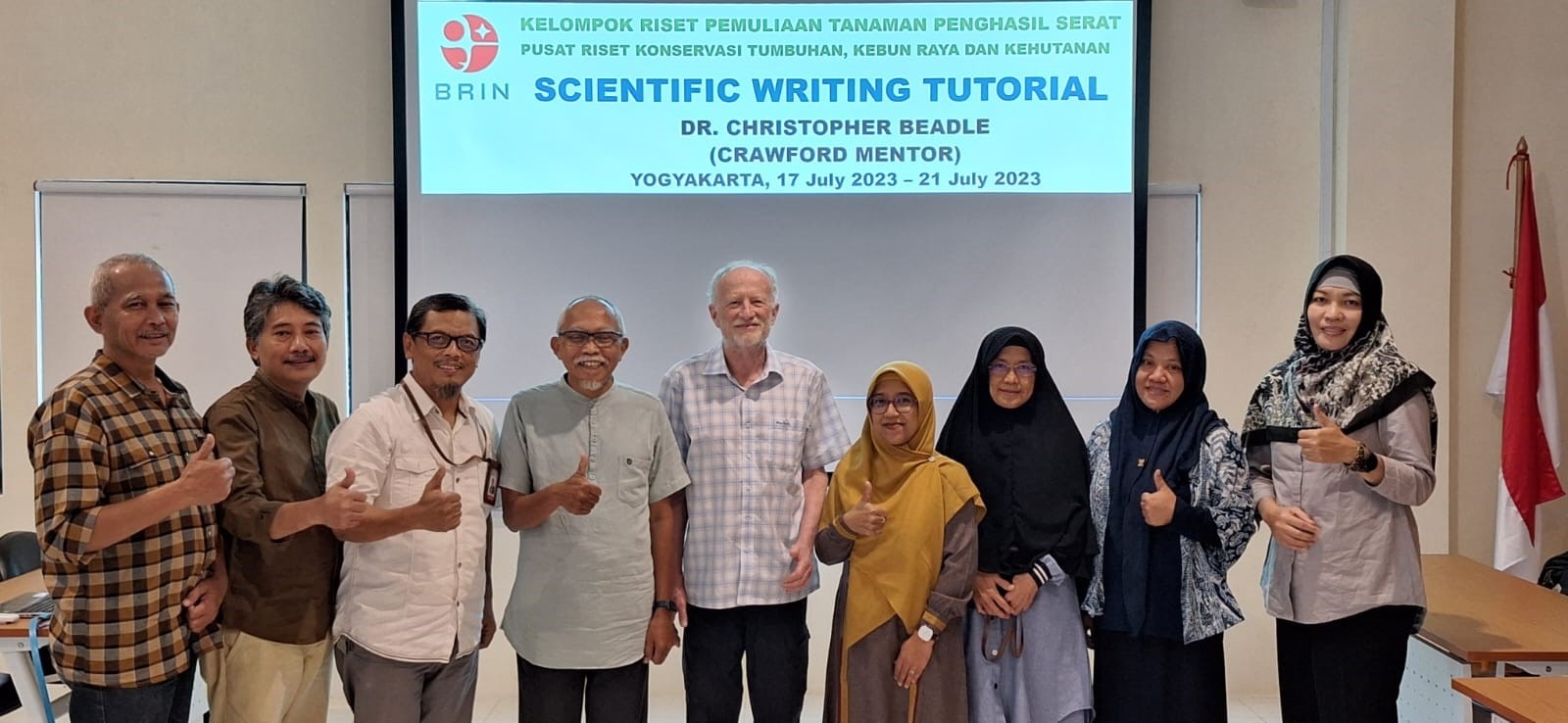

In a recent tutorial workshop sponsored by Crawford Fund for seven National Research and Innovation Agency (BRIN) staff in Yogyakarta, Indonesia, a first key learning was an understanding of the discipline required to meet the requirements of the main sections of the paper: the Introduction, Methods, Results and Discussion which are respectively about “why did I do it, what did I do, what did I find, and what does it mean?”

Other learnings were the art of writing in a logical order, the crucial need to define terms, avoidance of repetition, and to make the paper interesting and easy to read. Finally, the paper had to offer original information and be written in such a way that it was adding new understandings about the topic being studied. That all statements being made were accurate and properly referenced was a must, and the use of copy and paste approaches to writing needs to be avoided as this often leads to potential “plagiarism”.

No papers were finished in the week allocated, but the mentor is staying with the authors until the paper is ready to be submitted, by which time the intention is that the manuscript is in good shape and will have a high chance of being accepted and once published, cited! That said, there is still a lot of hard work ahead before that goal is achieved.

For many scientists, writing papers is often the most confronting professional task they have to address, but you only learn by writing, and then as frequently as possible, or the art is lost.